Spring is in the air, and the world is turning green once again. Spring is also the time when many waterfalls tend to run at their fullest, so now is an ideal time for photographing waterfalls. I’ve taken advantage of some of the flow already, though a few weeks more will bring brighter and more lush vegetation surrounding these lovely natural features.

If you haven’t tried your hand at shooting waterfalls, or are looking for some help in getting the most out your waterfall photos, here are some important things to keep in mind.

A Tripod is a Must

It may seem obvious, but waterfalls are one of the subjects that really requires a tripod for the best images. Not only because many waterfalls look best when shot with longer exposures to provide a nice smooth look to the water, but also because the best compositions for waterfalls are very often in positions that are extremely awkward to hand hold. Having a good tripod is also a necessity. Often the terrain will be uneven, and often the best compositions come from standing in the stream itself, so being able to precisely place the legs and having a tripod that will keep the camera steady even with the flow of water around the legs is essential.

One major point: if you’re going to go into the stream, please make sure that it is both safe to do so, and that your actions won’t damage the banks or any vegetation. You’re there to record the scene, not leave your mark on it. The above shot shows my tripod while I was shooting images at Blue Hen Falls. The stream has a slate rock bed, so I felt comfortable in my waterproof boots shooting down in the stream. If there are soft banks or fragile plants, please keep to any trails. See the image below that was captured from this position.

Polarizing and Neutral Density Filters

Polarizers and neutral density (ND) filters are the two filters that both truly still have a place in any photographer’s kit in the digital age. While other filters can have their effects replicated with digital postprocessing tools or multiple exposures, these two filter types can’t be faked, and both come in very handy for shooting waterfalls.

First off, let’s talk about the polarizing filter. A circular polarizer is something every outdoor photographer should have in their bag. The filter works by cutting out light of a certain polarization that is reflected off of surfaces. Rotating the filter allows you to choose which angle of light polarization is cut out. The result is the ability to remove glare from water, darken blue skies and increase saturation on damp or glossy vegetation. When shooting around waterfalls, almost all the surfaces will have some moisture on them, and therefore reflecting glare is very common. While images without a polarizer will look fine, being able to cut that glare can dramatically improve the look of a photograph.

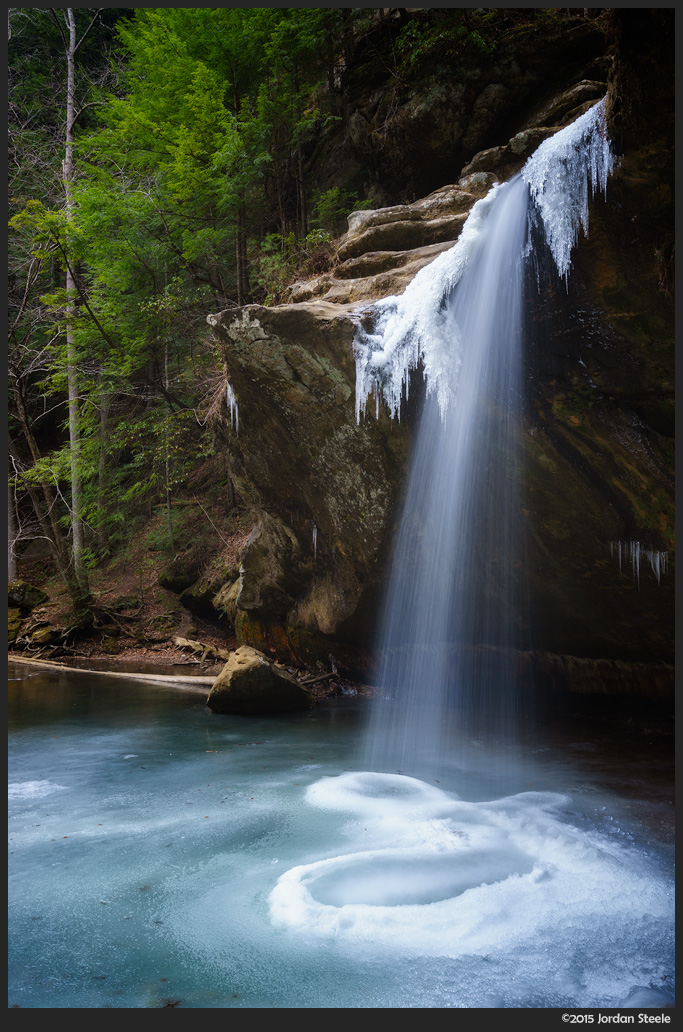

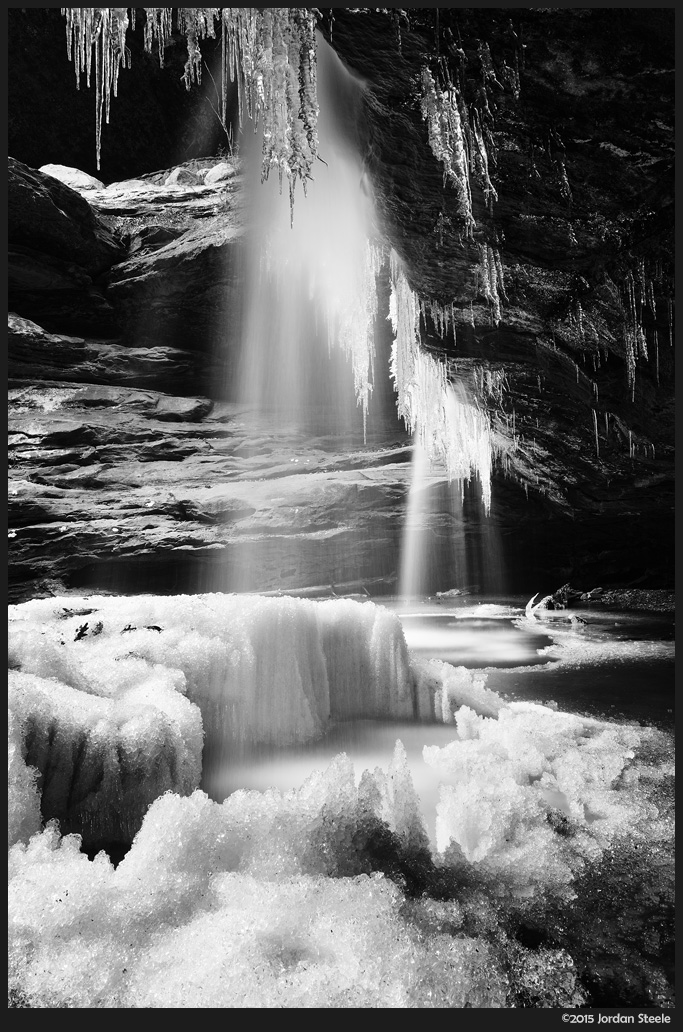

For a prime example of the effect of a polarizer, take a look at the images below. These images were taken from the exact same location within 20 seconds of each other. The only difference is that I attached my polarizer between exposures. The first image shows the scene without a polarizing filter. It’s a fine shot, but the colors are muted, only green and brown come out, and there is pretty heavy glare off the sides of the rocks and a strong reflection in the pool at the bottom of the image.

Now, take a look at the result with a polarizing filter. The processing on the two images is nearly identical (I did some finer color correction on the one below, since it was the one I finalized for print). The glare on the rocks is gone, showing the texture of the stone. The glare on the water is also gone, allowing the blue color of the water to shine through as well as extra detail in the sandstone gorge bottom. The overall effect is striking.

Another filter worth packing for waterfall shooting is a neutral density filter. Simply put, an ND filter simply lets less light into the lens, without altering color balance. ND filters are available in a variety of strengths, from 1-2 stop filters useful for cutting back the light a bit, all the way to 10 stops or more that can allow for minutes long exposures in mid-day sunlight. Using these filters can allow for longer shutter speeds to blur water movement, even when it’s bright outside. For most shooting of waterfalls, a 3 or 4 stop filter comes in quite handy. This should allow for exposures of at least 1/2 second in daylight, when stopping down the lens to f/11 to f/16.

Exposure Tips

Since we’re on the subject of lengthening shutter speeds, let’s talk about exposure time. There’s a few different schools of thought when it comes to how long you should expose a waterfall, with quite a lot of people enjoying the silky look of a long exposure, while others find that look cliché or ugly. I personally quite enjoy the smooth water look for most waterfalls, but it really depends on what you’re trying to show in your final image. Freezing the motion of a waterfall can often be rather ugly aesthetically, while in other cases a long exposure will eliminate too much detail. However, in both cases, it’s up to the photographer to judge based on the scene in front of them. The shot below was shot at 0.4 seconds, which was about the longest I wanted to let the shutter open on this shot. The falls had extremely heavy water flow, and anything longer just blurred far too much detail out of the image.

For my own shooting, I often end up shooting very early in the morning, especially in areas where there’s a fair amount of tourism, as I don’t have to deal with people walking in and out of my frame. As a result, I often deal with long exposures by necessity. For most of the waterfalls in Ohio, which often don’t have a super-high flow, the silky look of a long exposure works best anyway. I do think, however, that heavy flowing waterfalls demand a shorter shutter speed in most cases. First off, a shutter speed of 1/2 second or so will still show plenty of motion, but will also help capture some of the power of the falls. For really huge waterfalls crashing on rocks, very short shutter speeds might be desired to really capture the power of the water. Often, exposures of 1/2 to 2 seconds are great. For a serene or sometimes surreal feel, longer exposures can also be excellent. Experiment and determine what you like best.

Composition Tips

Here are a few other things to keep in mind when shooting waterfalls. First of all, shots of the main cascade of a fall can be very nice sometimes, but often they can be sterile or boring if there’s nothing leading your eye into the frame.

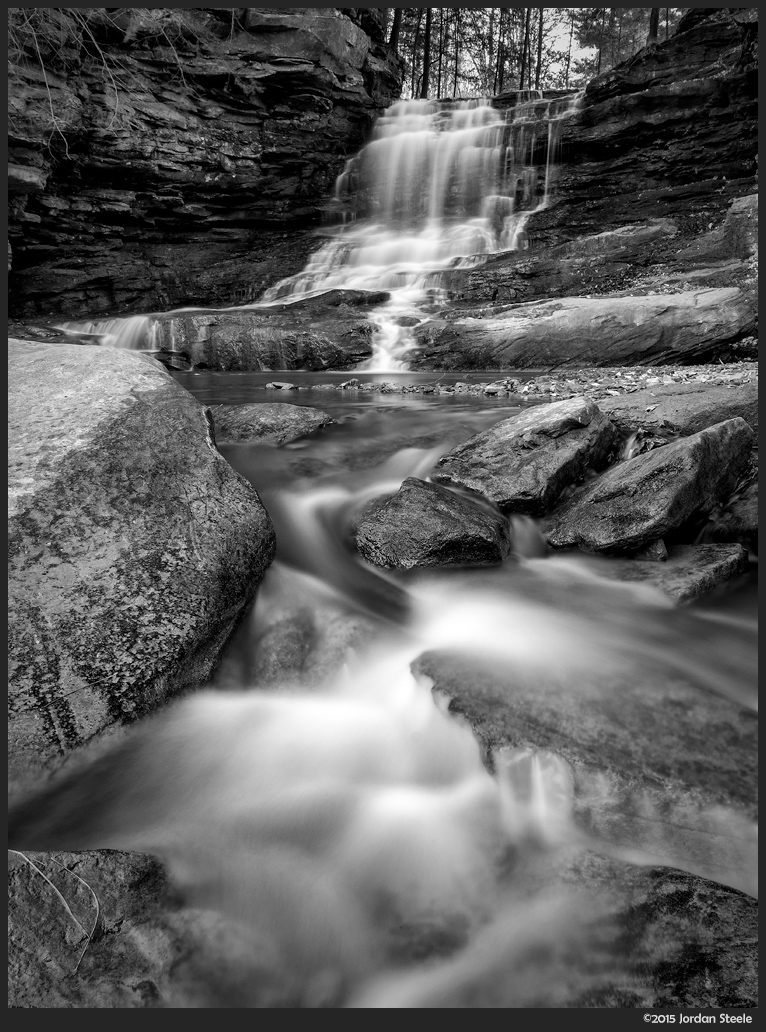

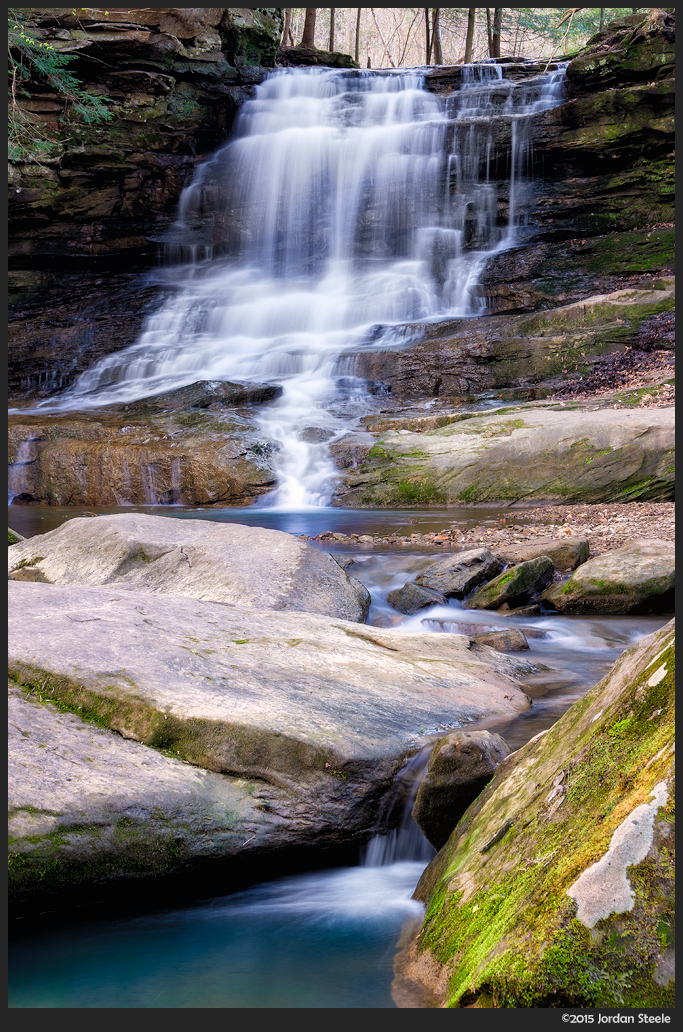

Keep an eye out for minor cascades below the main falls. Often these will switch back and forth, creating far more interesting patterns than the main cascade. It’s worth exploring lots of different angles, trying to visualize how your eye leads into the frame before setting up and taking the picture. The shot below, taken this morning, illustrates this perfectly. I took shots from about 6 different angles in this area today, and then I’d review the image and try new compositions, though most were small refinements on this scene. I finally managed to find the angle that reached the proper balance, with lots of foreground interest leading your eye into the frame.

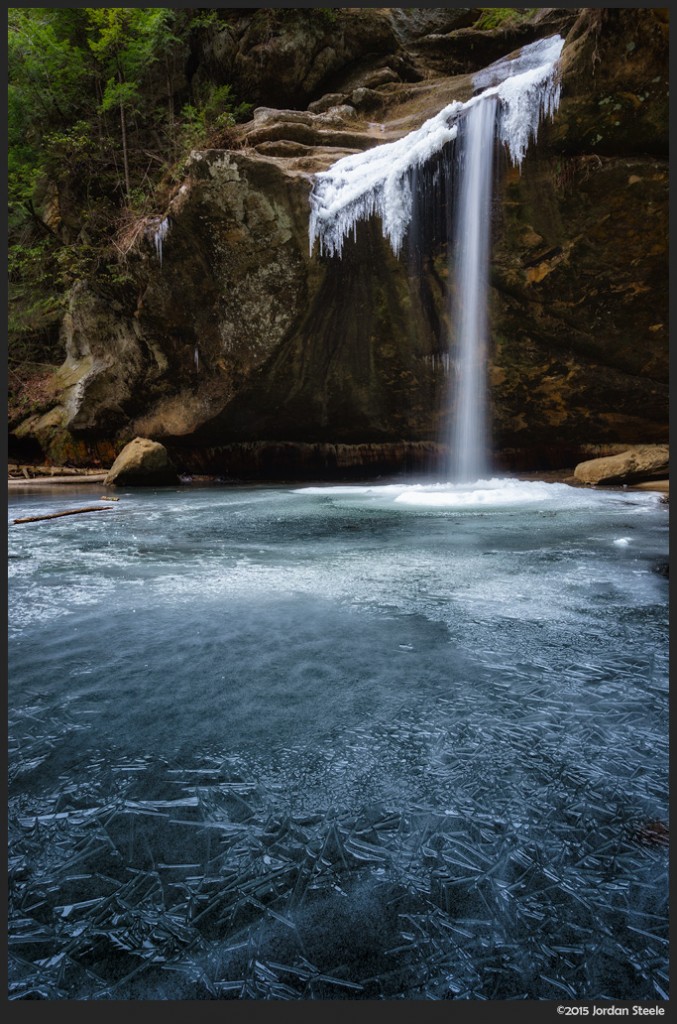

Second, context for an image can also help set the scene. Perhaps there’s a bridge nearby, or leading rocks. Often there may be a stark clifside next to the falls, or ferns or other interesting plants along the stream bank. Using these elements to help frame the waterfall can add another dimension to the shot. For the shot below, I positioned the camera very low, sitting on the frozen pond below the falls, focusing on the patterns in the ice, helping set the scene of winter despite the lack of snow. Experiment with different scenes and different looks. There are times I’ll work a single waterfall for two hours, finding all sorts of different ways to look at a scene. Don’t forget to have fun!

Image Samples

Finally, I thought I’d share a few more waterfall shots of mine from this year so far. Click an image to enlarge. Happy waterfalling!

Leave a Reply