How wide can an ultra-wide go? It’s a question you’ll find yourself asking when you get ready to mount the Voigtländer 10mm f/5.6 Hyper-Wide Heliar: the widest rectilinear lens ever made for a camera. As soon as you look through the viewfinder with this lens mounted, you’ll have your answer: almost unfathomably wide.

The 10mm f/5.6 is a one-of-a-kind lens: the first lens ever made with a 10mm focal length to cover a full-frame sensor that isn’t a fisheye lens. Fisheye lenses are still the ultra-wide champs: they can cover a full 180 degrees corner to corner, but with the unmistakable bowing of straight lines to accomplish the feat. This Voigtländer lens sets a new bar in rectilinear width, besting the 11-24mm Canon lens that made headlines when it was announced last February. Prior to that lens, there were a small handful of lenses with a 12mm focal length (and Sigma had an APS-C equivalent 8mm lens). But 10mm has been unheard of before now. While a 1mm advantage may sound small, with focal lengths this wide, it’s a visible difference in field of view. The 11-24mm goes as wide as 126.5 degrees, while the 10mm f/5.6 increases that 130 degrees.

Perhaps most impressive is that this new Voigtländer for the mirrorless Sony E-Mount fits a lens of this extreme width into a relatively lightweight and compact package: it’s less than 3″ long and weighs 371g, while costing $1,099 US. By comparison, the previous wide-king, the 11-24mm, is over 5″ long and over three times as heavy (1,180g), while costing a whopping $2,899. Still, none of it means anything if it’s a terrible performer, so let’s cut to the chase and dive in.

Construction and Handling

The Voigtländer 10mm f/5.6 Hyper-Wide Heliar is reminiscent of Voigtländer’s rangefinder lenses for the past decade. It’s constructed of solid metal, and the lens both looks and feels impressive in the hand. It’s a bit larger than I thought it looked in pictures, but given the extreme width, it’s remarkably compact. The 10mm f/5.6 has electronic contacts at the rear of the lens, but make no mistake, this is a fully manual lens. Much like Zeiss’ Loxia line, the 10mm f/5.6 uses the electrical connection to pass EXIF data such as set aperture and focal length (which is useful for the A7 Mark II series in-body stabilization), as well as to activate auto magnification during focusing.

The lens has a built-in metal lens hood that can’t be removed, and there are no filter threads, as the extreme width and bulbous front element precludes front mounted screw in filters. To cover the lens, a metal lens cap that fits over the hood is included, and fits very securely.

The lens has two main controls: a front mounted aperture ring which moves with distinct and moderately firm detents, and a very smooth and moderately damped focus ring. Given the tendency to set focus and forget it, given the very deep depth of field, I wish the focus damping were a bit stiffer, but it’s not bad. I found that for most stopped down work, focusing between 1m and 2m yielded images that were sharp from near to far. I generally only focused more precisely if the point of focus was very close up. The lens focuses to 0.3m, which, given the extreme width, I felt could be a bit limiting if your goal was to make small items big while capturing an expansive view behind the subject. At closest focusing distance, the field of view covers an area of several meters, so isolating flowers or other small items isn’t going to be possible with this lens.

There’s a nice feature built into the aperture ring of this lens. Like several other Voigtländer lenses, such as the Nokton series for Micro 4/3, the 10mm f/5.6 has the ability to declick the aperture ring simply by pulling the ring towards the front of the lens and rotating it until the yellow tick mark (seen in the image above) is centered.

Using a 10mm Lens

Using an ultra-wide angle lens is often challenging for many photographers. There is so much captured that it can sometimes be hard to find pleasing compositions. Some people have a hard time ‘seeing’ in ultrawide, and the extreme field of view also increases the appearance of perspective distortion when the camera is tilted. All of these challenges are here with the 10mm f/5.6, but they’re magnified tremendously. Tilt the camera just a hair away from level, and converging lines become very obvious. It’s up to you to decide whether those converging lines will add to the composition or detract. Objects even moderate distances away appear small, so very careful thought must be given to how the elements in your image align. Although I think I have a very good eye for ultra-wide composition, even I was a bit worried before the lens arrived that I’d have trouble finding uses for something this wide.

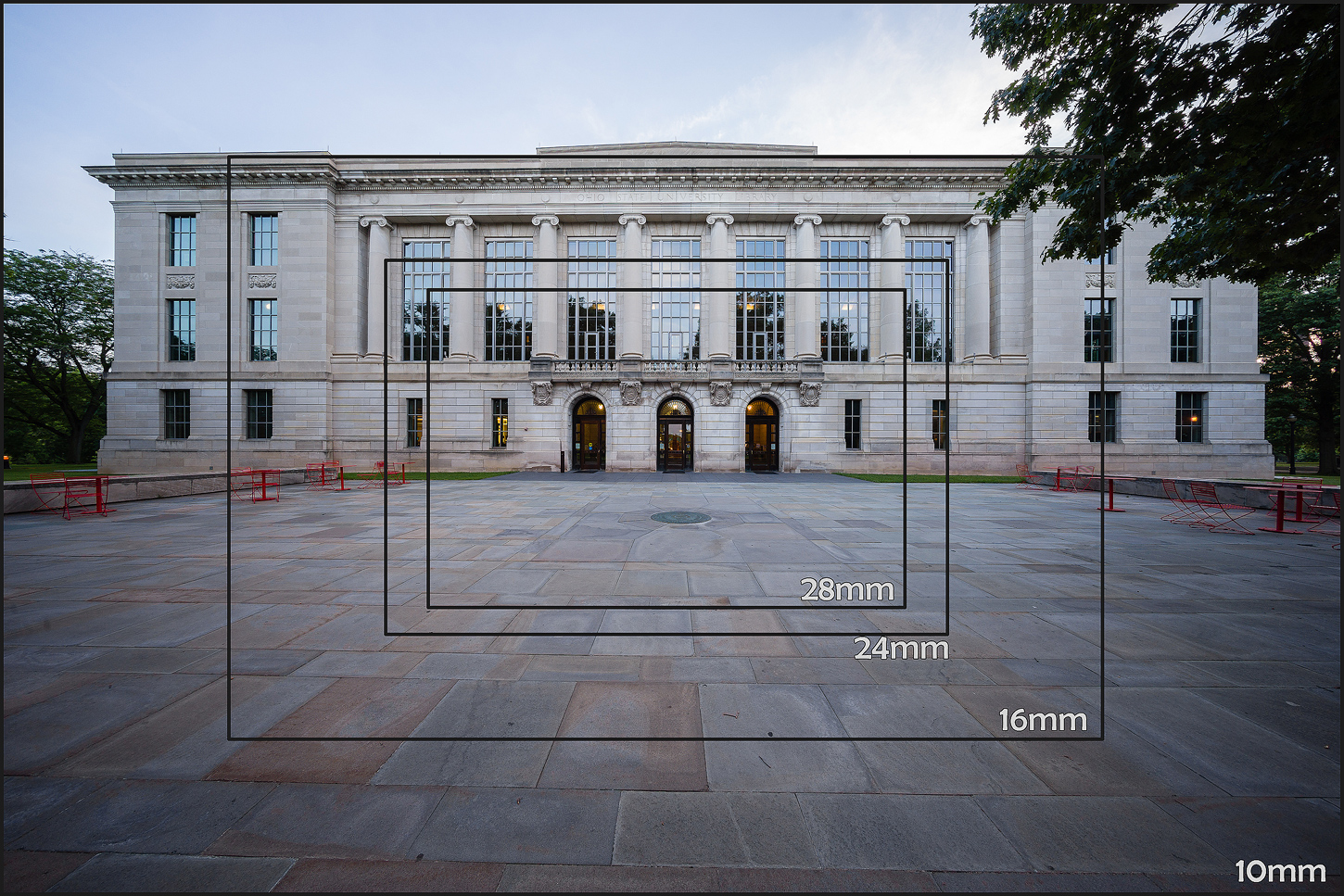

A lot of landscape work requires longer focal lengths to isolate the scene a bit. By longer, I mean 16-50mm on full-frame. That may sound odd, but after using the 10mm f/5.6 for a while, even 16mm ultra-wide begins to look almost like a telephoto. It’s a crazy perspective. The shot below shows the relative fields of view of various wide-angle lenses. I took shots from the same location on a tripod with the 10mm, followed by several focal lengths with the FE 16-35mm. The 10mm’s field of view makes the already very, very wide view of the 16mm end of my FE 16-35mm look downright pedestrian. The super-wide 24mm focal length almost looks like a telephoto in comparison to the expansive width of the 10mm Heliar. I was standing fairly close to this building, but the width makes it seem fairly distant.

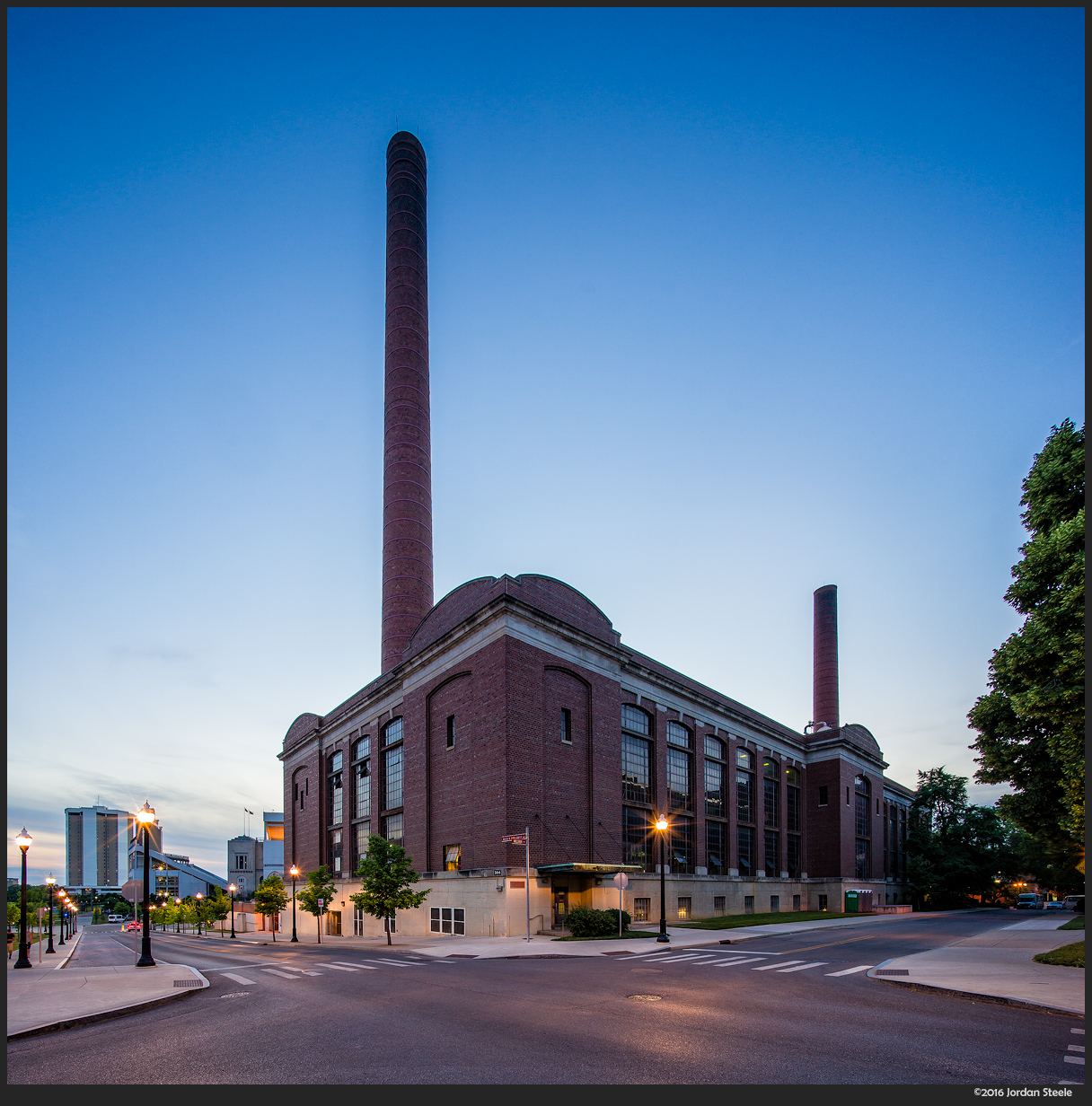

Thankfully, I found that this lens is exceptionally well suited for dramatic interior photography, as well as certain creative uses outside. It’s also wide enough that if you are OK cropping a fair bit out of the image, you can utilize the lens as a stand-in for a tilt-shift ultra wide, as the width covers the same field of view as a 15mm shift lens would cover at a full 12mm shift. As such, you can use the lens to shoot architectural shots like the one below, without having to correct the verticals in post.

In all, the lens can be somewhat challenging to use, but is eminently rewarding if you can train your eye to see the compositions that are possible with it. Over the course of my time with the lens, it quickly became an incredibly fun lens to use. It just can do things that no other lens can. I fell in love immediately with the capabilities, and while I didn’t think I had a need for a lens this wide, in just two days, I knew I’d have to own one for myself. But I’m getting ahead of myself. Let’s dive a bit deeper into the optics of this lens.

Leave a Reply