Today I’m going to set the record straight and correct a myth that seems to persist throughout the photography world. I’ve seen this fallacy repeated many, many times, both by novice photographers as well as by seasoned professionals, and that is the myth that a certain focal length will project a specific perspective.

This fallacy is most egregious when used during format comparisons, where uninformed photographers will argue that they prefer Full-Frame because an ’85mm lens gives a true 85mm perspective’ and a smaller format has the perspective of a shorter lens even though field of view is the same. Heard that or something similar before? Well, it’s bunk.

What is Perspective

In a photograph, perspective is the relationship between foreground and background elements and how they appear in relationship to each other in the photograph. You may notice that shots taken with a telephoto lens may include your subject and background elements that are far away, but the final result appears very flat…as if the background and foreground elements have become compressed. This is often referred to as telephoto compression. The photo below shows a good example of a compressed perspective, the boat sits by the dock, but the city behind doesn’t feel too distant. It’s been ‘brought closer’ by the short telephoto lens, as if the scene has been compressed a bit.

Likewise, in many wide-angle photographs, foreground and background elements appear further away from each other than in real life…the foreground elements appear larger, the distant background elements appear very far away, as if the world has been extended away from the viewer. The shot below was taken of the same general subject with an 8mm fisheye lens, providing an extreme 180 degree corner to corner view. The boat appears enormous in the frame, while the world in the background is very small, as if the landscape has been stretched and expanded.

These perspectives are real and tangible, and easily shown in these examples, so why am I saying that perspective based on focal length is a myth? Because it is…

The Myth

Simply stated, there is a commonly repeated statement that perspective in a photograph depends on the focal length. Longer focal lengths provide a compressed perspective, while short focal lengths provide an extended perspective. This is a tricky thing because the myth has a basis in reality (as shown in the examples above), but the misconception occurs when the photographer thinks that it is the actual focal length of the lens that causes a change in perspective. In reality, the lens focal length itself has nothing to do with perspective, at least not directly.

This myth is further compounded by photographers who think that it’s not even field of view that matters, but that, say, a 135mm lens has a certain amount of compression, while, say, a 68mm lens on Micro 4/3 would have half that level of compression even though the field of view is the same. I’ve seen this misconception spread repeatedly.

Case in point: a comment on Imaging Resource’s first look for the Panasonic 42.5mm f/1.2 for Micro 4/3 states: “However we are now going to be inundated with a bunch of “portraits” th[at] lack the proper compression of a true 85mm lens. Facial features and structure will still be rendered how they would with a ~35/40mm lens on full frame.”

If this were an isolated incident, I wouldn’t be writing this article, but I’ve seen the above statement (with various other lens examples) over and over this past year.

The Fallacy

The cause for this confusion is a version of the logical fallacy cum hoc ergo propter hoc (Correlation proves causation). That is, if A occurs in correlation with B, then A causes B. How it relates in terms of perspective in photography is such:

Photographers see that for the framing of an image they have in mind, the compression of the scene becomes more pronounced the longer the focal length that is used. Therefore, they assume that the longer focal lengths cause the compressed perspective.

However, there is a big difference between using certain focal lengths to get an image that has the perspective you want and those lenses causing the change in perspective. In fact, the focal length and field of view have no impact whatsoever on the change in perspective.

What changes perspective

So, if it isn’t focal length that changes perspective, nor even field of view…what is it? Well, there is a factor C that is the cause for the correlation of perspective and focal length:

Distance.

The perspective in a photograph is 100%, completely dependent on the photographer’s physical distance between them and their subject and the other elements in the scene. That’s it. Not the lens, not the format, nothing but the distance.

To create an image with telephoto compression, the photographer backs away from the subject and uses a longer focal length to keep the framing the way they want. The key point is: It’s the backing up that changes the perspective, not the lens.

If I am 1 foot from my subject, and the background is 100 feet behind, and I frame the subject with an ultra-wide angle lens, the ratio of distance between me and the subject and the subject to the background is 1 to 100. Now, if I back up 10 feet and frame the subject so they’re the same size in the frame as my original composition by using a short telephoto lens, now that ratio is only 1:10. This causes the background to appear much closer to my subject than in the first instance.

When we take photos with a wide-angle, we usually shoot from closer to our subject…in the case of the fisheye shot above, I was less than 2 feet from the boat. In the telephoto shot, I was closer to 30 feet away from the boat.

I am amazed that this myth continues to persist because it is incredibly easy to test, and you don’t even need two camera formats. Simply shoot the same scene from the same location with two different focal lengths, then compare the common area between them. You will quickly see that the perspective is identical for a given distance.

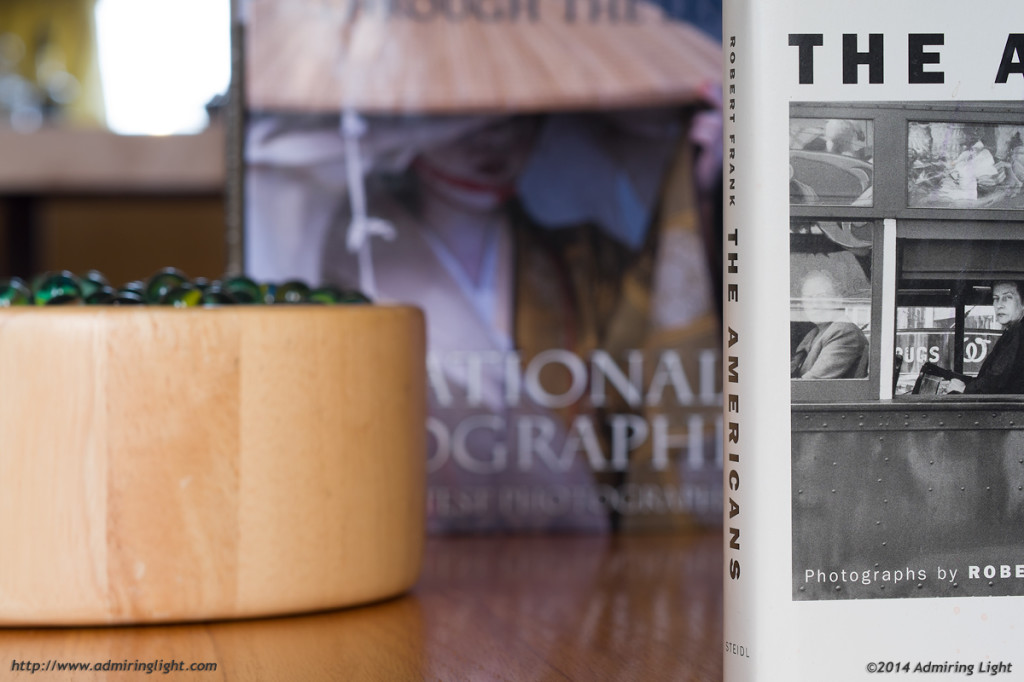

To illustrate this, I set my camera on a tripod, and shot this setup in my livingroom. First with the Fuji 60mm f/2.4, then with the 23mm f/1.4 at the same distance. I adjusted aperture to give similar depth of field so as to better compare perspective. (f/2.5 on the 23mm, f/6.4 on the 60mm).

Here’s the 60mm shot:

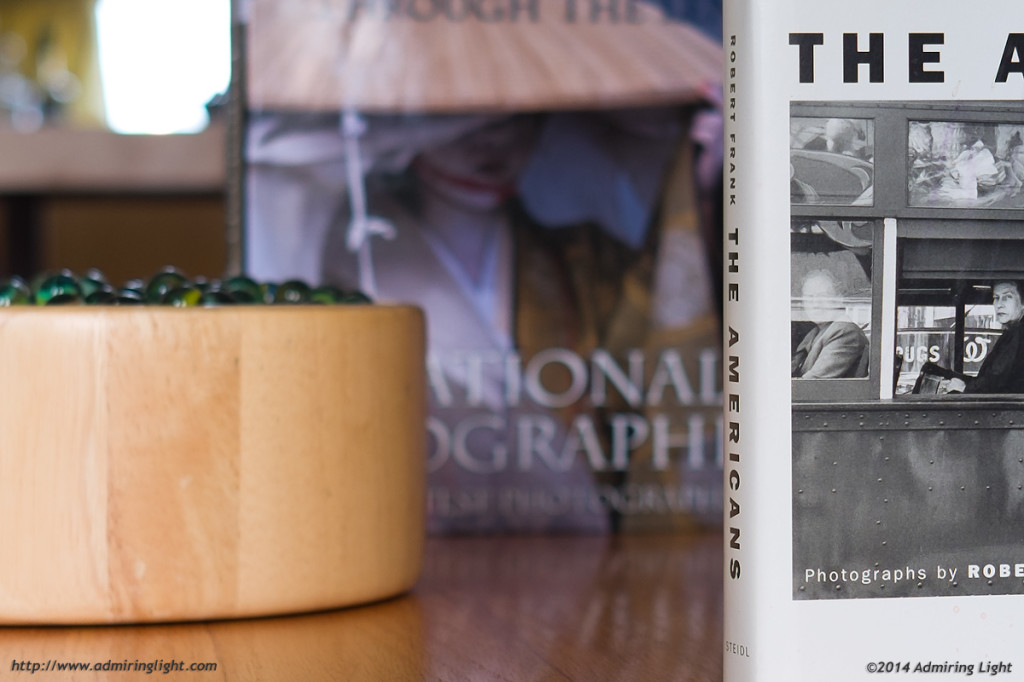

And here is the shot from the 23mm, cropped to the same area as the 60mm shot:

See a difference? Neither do I. The perspectives are identical; there is the exact same level of ‘compression’ in the cropped 23mm shot as there is in the 60mm shot, thus showing that the perspective relationship is solely dependent on where your camera is in relation to the elements in your photo. If you think about it, this makes perfect sense…how can things in real life align themselves differently based on what lens you put on your camera?

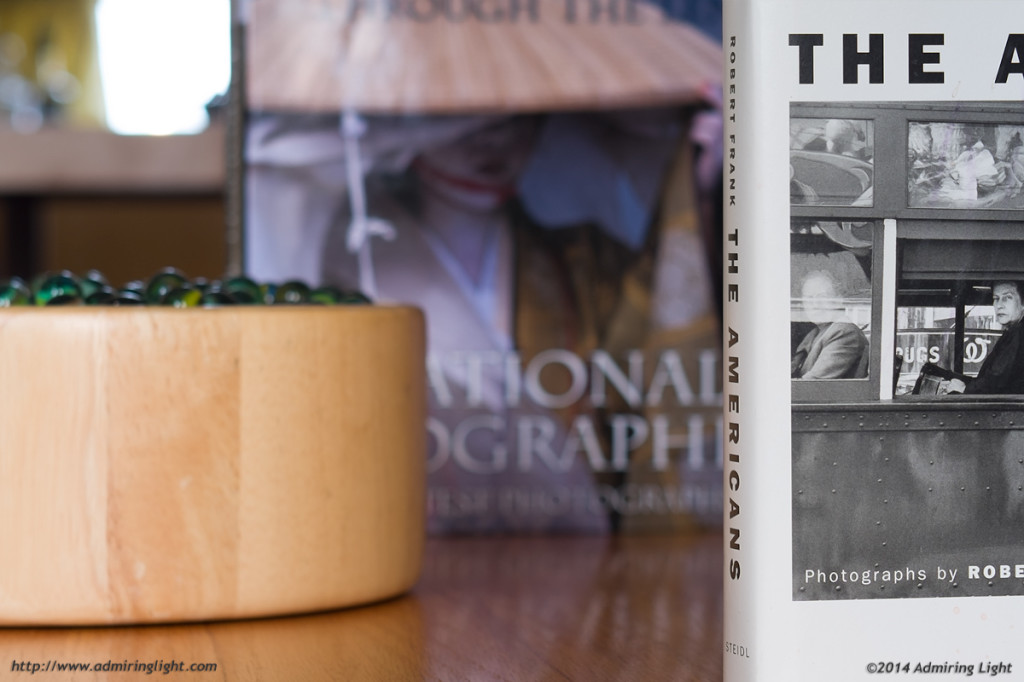

For those few who will still argue that they see a perspective difference in the above photos (and I always get some whose minds play tricks on them), below is a composite image of the above two photographs, with the 23mm shot overlaid on the 60mm shot, and set to 50% opacity. If there were any differences, they’d stick out like a sore thumb…and yet, well, just look:

The one thing I haven’t addressed yet is the one thing that is dependent on the focal length of the lens you choose: How much of the scene is captured. That, of course, will always be true, and it, along with the photographer’s positioning, determines the final composition of a photograph. But as I’ve shown here, it’s the positioning of the photographer that determines the perspective. It’s up to the photographer to properly use that position in conjunction with choosing a focal length to create dynamic photographs that have both the angle of view and the perspective the photographer desires for the final image.

A good read for everyone, but now I am admitedly a little confused about another myth. I thought that focal lenght does not affect depth of field in a significant way, but here you shot the same scene with very different apertures and the background blur appears the same?

Depth of field is depended on three things: focal length, aperture and distance to subject. The effect focal length has on depth of field is the main reason larger formats have shallow depth of field from the same distance and same aperture…you use a longer focal length to get the same framing.

You may be thinking about the interplay of depth of field and distance, where two lenses framed the same (on the same format) and shot at the same f-stop will have the same depth of field. This is true, and it works because you proportionally back up as you increase focal length to keep the framing the same. Depth of field will then stay the same, but background blur will be more for the longer lens (at the same f stop) because of a larger physical aperture, and as I discussed here, the perspective will change because of the change in position.

Four things, Jordan: don’t forget format! For larger formats you need much higher f-stops to retain the same depth of field. 😉

Format actually doesn’t impact it (well, it does, but not in the way you think). The reason larger formats have shallower depth of field for the same f-stop and framing is because you are using a longer focal length for the same field of view. If I use a 25mm lens for a normal perspective on Micro 4/3, and a 50mm lens on full frame, I’m standing in the same spot…if I shoot both at f/1.4, the full frame shot will have much shallower depth of field because I’m using a 50mm lens instead of a 25mm lens.

If you shoot a 50mm lens at f/1.4 on either format, interestingly enough, the SMALLER format will have shallower depth of field due to the different circle of confusion – the area is magnified more on output to the same size making the sharp/unsharp transition easier to view and therefore affecting what you will perceive as sharp. But that situation results in two very differently framed shots… Looking at it practically, the larger format will have shallower depth of field for the same f-stop, but it’s because of the longer focal length used for the same image.

Great post. I remember looking at a depth of field calculator for hours trying to figure out why a FF camera had a smaller DOF than a crop sensor until I matched the field of view. You read so much equivalence talk in forums right now that sometimes you get pulled into a false sense of comprehension. This is why 4/3rds will survive in the long term. People will still get great pictures and won’t know about all this theoretical equivalence that us “photo enthusiasts” get so worked up about.

Completely accurate. It’s really very simple.

You divide the focal length by the f-number and you get the aperture diameter. The aperture diameter basically tells you how big of an area you are blurring over. You double the f-number, or halve the f-number, you are quadrupling this area.

That simple…

50 mm f1.0 lens will have about the same control over depth of field as a 100mm f2.0 lens… They have the exact same aperture diameter wide-open.

Actually, there are four factors and the fourth is the oft overlooked circle of confusion. The full formula for calculating DoF will include this. What it does is show different DoF depending upon how accurate one wishes to be. For the highest quality work, select a larger figure, and for less demanding work, where the zone of relative sharpness can be acceptably greater, select a smaller figure.

Hi Jordan,

Nice post. I got annoyed by “professional” photographers getting it wrong too and summed up both the mathematical proof to point out that perspective depends only on lens to scene distance as well as taking sample shots to illustrate the point:

http://www.leavethatcouch.com/2013/12/28/someone-is-wrong-perspective-versus-focal-length/

http://www.leavethatcouch.com/2013/12/29/example-pictures-perspective-versus-focal-length/

I am amazed how resistant to facts some people can be…

Tobias

I visit your site quite regularly, as I think that it’s one of the more clever sites on the photoweb. I’m so glad that you brought that really pesky myth up, as I also stumbled upon the IR-article and wondered, if anyone noticed it.

Great article of yours and keep up your good work!

Thank you!

Good to read someone talking in an easy-to-understand manner, it was very informative!

This is a hard thing to communicate. I really think it’s because of the phrases we use to describe this. What are good, short ways to express “telephoto perspective” or “the perspective of a lens”? One part of the interaction you don’t talk about is sensor (or film) resolution. If resolution were infinite, you could crop from wide angle shots and not worry about it. Instead, you have to worry about “putting pixels” on a shot. It took many paragraphs to describe the interaction in a way that demonstrates that distance is the direct cause of perspective; “telephoto perspective” does it in two words. (And that shortcut implies that the direct cause is from the lens.) We need a better shortcut!

Great stuff. Much needed stuff even. People will argue this with me for days. And even if it was by accident the bokeh stuff is great info too. Focal lenght and subject distance play a MUCH bigger role than aperture ever will. It is not the sensor at all, it’s the lens and subject relationship

Actually, DoF is dependent only of the physical aperture diameter and focus distance (i.e. distance to subject).

Of course, the f-values in photography are defined as aperture diameter / focal length, since that is a very convenient way to express the light gathering ability of lenses.

Expressing the lenses’ apertures in f-stops makes the DoF dependent of focal lenghts too, just because f-stop is defined that way.

Hmh. I thought I’d replied directly to Jordan’s comment, but I guess not then.

This is actually incorrect. Go to a depth of field calculator and you’ll see that a 50mm lens at f/2 will have half the depth of field of

A 25mm f/1.0 at the same focus distance despite the same physical aperture size.

Depth of field is the same for the same framing and same f/stop (on the same format) Amount of background blur is dependent on physical aperture size. They are related, but not the same thing.

Another educational and well written article. Even an ignorant like me, with poor knowledge of english language, was able to understand the concept!

Thank you Jordan and keep going

I had the same discussion with Mike Brown, a professional photography instructor who doesn’t know the difference between a point of view and a line of sight>

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7SCBMaJliUU&feature=autoshare

This is his second instructional video on the matter and he still insists on his wrong understanding, passing it on to devote fans on Youtube. What a sad world.

Yeah that guy is wrong about so many things:

-Lenses compress perspective.

-Point of view isn’t changed if you walk 20m further away

-etc…

ugh…

Good presentation of a frequently misunderstood subject, but you’ve only tackled half of the subject!

The thing that gives a ‘wide-angle’ or ‘telephoto’ perspective is actually the viewing distance. If a photo is viewed at a distance proportional to the focal length of the taking lens, the perspective will appear ‘normal’.

And that’s how we change the view – as you show in your examples. But get really really close to the screen for the fish-eye shot and 7.5x as far back from it for the long shot, and each will look ‘normal’ – just not at the same time!

The fun of wa and tele shots is that we know they will be viewed at ‘normal’ distances and relish the apparent perspective distortion.

Good shooting

Mike

Hello, Jordan.

I’ve already posted a short comment, but I was pointed in the direction of you site during a lively debate on this very topic on the SteveHuff photo site, and this is currently running. The tele lens causes compression myth is running there as well, and started by Steve actually posting this comment.

I, and a few others, have tried pointing him in the right direction, as anyone can see if they care to have a read and chuckle at the various posts. I use my same ID as here: TerryB. Here is the link if anyone is interested.

http://www.stevehuffphoto.com/2014/03/31/the-panasonic-leica-nocticron-42-5-f1-2-lens-review-comparison/

First impression of your site are very promising and I’ve added to my list of favourites to come back to delve deeper.

Best wishes,

TerryB

I see a lot of interesting posts on your website. You have to spend a

lot of time writing, i know how to save you a lot of time, there is a tool that creates unique,

SEO friendly posts in couple of minutes, just type in google – k2 unlimited content

Mind = blown. Thanks Jordan! This is why I regularly visit your site. I’ve had this wrong for 20+ yrs. Your ability to explain a potentially confusing subject is exceptional.