Viewfinder and Rear Screen

The EOS R8 inherits the RP’s 0.7x magnification 2.36 million dot EVF. By today’s standards, it’s a low-end finder, and it certainly is visibly smaller than the rather large viewfinder in many other full-frame mirrorless cameras. However, it’s still a reasonably good finder, and I don’t mind taking a slightly lower end EVF in this camera, which I’m sure helped Canon include all the other goodies and still hit the sub $1,500 price point.

The Viewfinder is still reasonably large, and clear enough for shooting in most any light. The EVF by default refreshes at 60fps, but can be turned up to 120fps, at the expense of battery life. For me, that tradeoff is worth the battery hit, as it provides a much clearer and more responsive view. It’s not going to wow anyone who has used a newer high end mirrorless body, but it certainly gets the job done without hindering usage.

The rear screen is also the same 1.6 million dot, 3.0″ touchscreen that is found on the RP. This screen is bright and clear, and has full articulation – allowing you to see the live view from most any position, including from the front of the camera. The touch controls are responsive and intuitive. Despite being a little smaller than the screen on something like the R5, this is still an excellent panel.

Autofocus

Up to now, I’ve discussed the R8’s physical features and controls, and I’ve talked a lot about things that are shared with the decidedly entry-level and somewhat dated EOS RP. Now we get deep into more of the things that make the R8 a powerful and compelling camera, and that begins with the autofocus system.

The EOS R8 shares the same sensor, processor and autofocus system with the more expensive EOS R6 Mark II, which itself inherits a lot of its autofocus DNA from the flagship R3. The autofocus uses Canon’s Dual Pixel AF II, with enhanced tracking and subject recognition beyond that which first appeared in the R5 and R6.

If you’ve used either the R5 or R6, the AF system works very similarly, but with most things just a bit better. I’ve found subject recognition to be more sure, and stickier on the eyes of human and animal subjects. The whole area tracking Servo AF setting allows you to use whatever focus point mode you want, and then have tracking take over, and also recognize subjects in the frame as well. It’s a hybrid of Canon’s previous tracking when setting initial point and standard Servo AF with a selectable point, and functions quite similarly to Sony’s Real time Tracking AF mode.

One very nice benefit to the R8’s autofocus system is that it allows for a wider focus area on the RF 800mm f/11. On the R5 and R6, the 800mm is limited to only focusing in a central square that takes up approximately 50% of the frame. On the R6 II and now the R8, that area has expanded to a rectangle that fills approximately 80% of the frame, which makes the lens far easier to use when tracking wildlife.

I found tracking accuracy on moving subjects to be very good, and a slight improvement on the already excellent autofocus from the R5. The system can also maintain focus on the subject even when distracting elements get in the way. While shooting some birds along a river, I was tracking a duck landing, and noticed it was headed for another duck to fight (the shot above). I shot the entire sequence, from landing to finish, and the camera maintained focus on the ducks, even with huge amounts of splashing water obscuring them.

On the down side, I did notice that in dim light, the R8 isn’t quite as quick at locking focus as my R5. It still is accurate and works fine, it just takes a tick longer to finalize the focus point, especially with a slower focusing lens like the RF 35mm f/1.8.

Performance

While Canon has limited a few things with regards to performance, the R8 also largely maintains the same outstanding performance of the R6 Mark II as well. The camera uses the same Digic X processor found in the R5, R3 and R6 Mark II, and that means the camera is fast and responsive in everyday use, and image processing is fast as well.

Canon makes good use of the excellent autofocus system, as the continuous burst rate maxes out at an astonishing 40 frames per second with electronic shutter. In electronic shutter mode, one can shoot at 40 frames per second in H+ drive mode, 20 frames per second in H, and then at a maximum of 6 frames per second with the mechanical shutter. Note that the R8 lacks a two curtain mechanical shutter, but rather an electronic first curtain shutter (EFCS), with mechanical second curtain. When I refer to the mechanical shutter in this review, I am referring to EFCS.

While the mechanical shutter does not have an exceptionally high burst rate by modern standards, it’s still reasonably quick for a lower mid-range body. The electronic shutter, however, is quite usable for a wide variety of action shooting. The R8’s readout speed is approximately 1/70s, which is faster than the original R6 and the R5. It isn’t as fast as the stacked sensor of the EOS R3, but it’s still fast enough to provide natural looking images of things like birds, running people (see shot above), and other action. You will not want to use it for fast ball sports like tennis or baseball, due to rolling shutter. If panning on very fast moving subjects, you’ll also see some slanting of the background (this can often be corrected in post, however).

One area where Canon differentiates the R8 from the R6 Mark II is in buffer size, where the R8 has a notably smaller buffer than the R6 II. With that said, the buffer on the R8 is still rather good, especially for a camera in this price range. If shooting at 6fps with the mechanical shutter, the buffer is essentially unlimited for JPEG, RAW or cRAW shooting. With the high speed electronic shutter modes, you will run out of buffer moderately quickly in the fastest shooting modes. Below is a table of maximum bursts before slowing, in my experience with the R8 using a Sony Tough M 64 GB UHS-II card, rated for 150MB/s writing:

| Frame Rate | # of Shots before Slowing (RAW) | # of Shots before Slowing (cRAW) |

| 6 fps (Mechanical) | Unlimited | Unlimited |

| 20 fps (Electronic) | 60 | 121 |

| 40 fps (Electronic) | 54 | 98 |

While you will run out of buffer after a little more than a second when shooting at full RAW and 40fps, that can be extended to two and a half seconds by using the cRAW setting, which has essentially no visible impact on file quality. Switching to 20 fps gives you over 6 seconds of continuous burst before slowing. Most of the time I shot at 20fps for action shooting, and as such I never really ran into any buffer issues with the camera.

It’s interesting to note that Canon’s flagship sports DSLRs didn’t exceed the R8’s buffer depth at their top speed until the 1DX Mark III in 2020. The 1DX Mark II had a buffer depth of 57 shots at 14 frames per second in RAW, falling 3 short of the R8’s 20fps buffer depth. The original 1DX had a buffer of only 38 RAW files at 12fps, while the 1D Mark IV could only shoot 28. It’s truly amazing what modern cameras are capable of.

RAW Burst Mode

A feature that first made its appearance on Canon cameras with the professional grade R3 is also present on the EOS R8: RAW Burst Mode. This is a special mode that needs to be activated in the menu system, and it allows the camera to take a 30 fps burst that begins a half second before the shutter was pressed. It accomplishes this by beginning a rolling buffer of RAW images that continually captures 30 fps bursts, overwriting themselves every half second. When the shutter is depressed, it saves the 15 frames captured before the shutter was pressed, and then however many you shot afterwards.

This is a great feature to capture images that are otherwise just exceptionally difficult to get, such as lightning strikes (with short shutter speeds or without a lightning trigger), birds taking off from a branch, or any other situation where the action happens quickly and unpredictably.

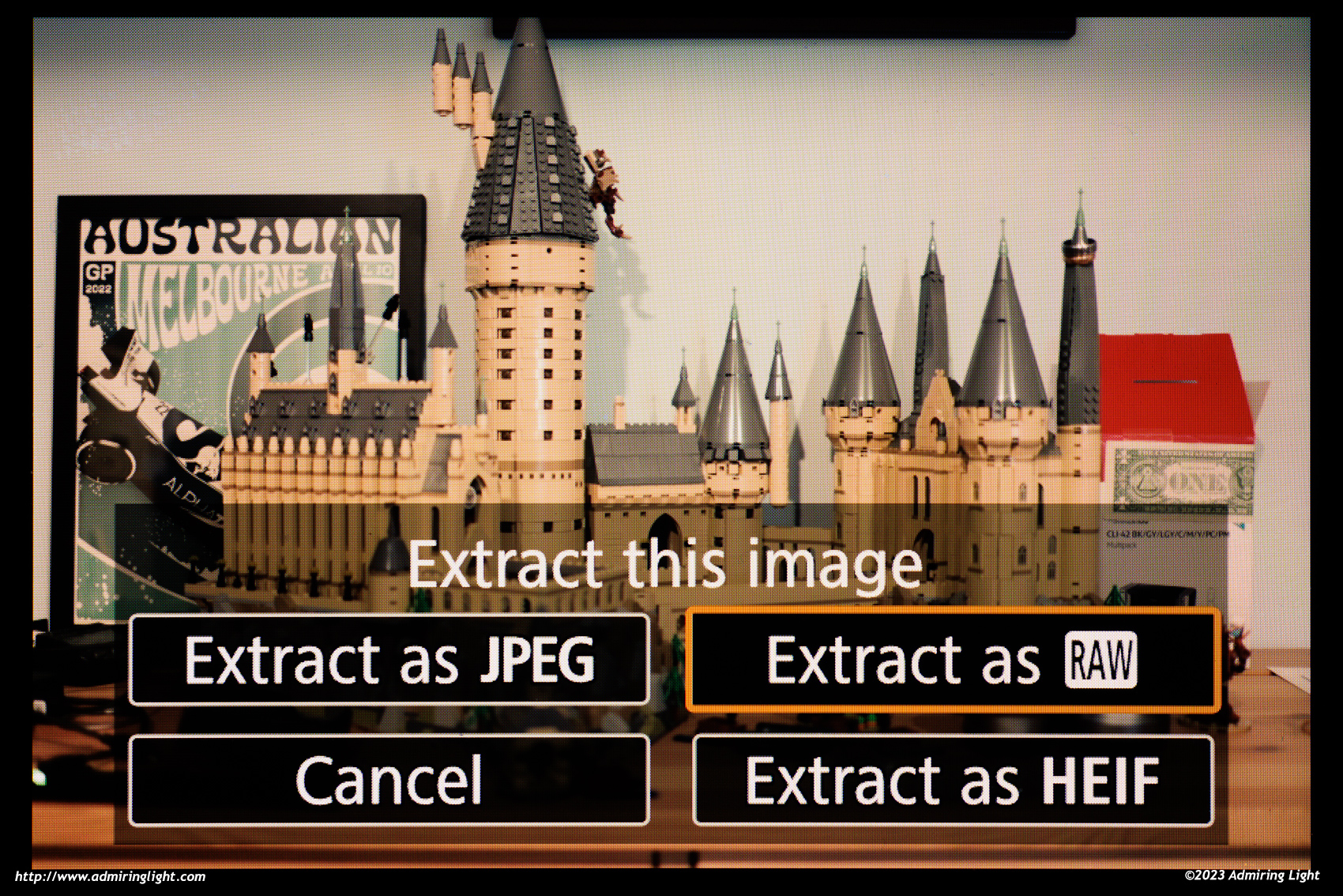

There are a few downsides to this feature, however. First, all the RAW files captured in a burst are combined into a Burst Stack, which is a single file. This file is unreadable by third-party RAW converters, and so can only be processed directly using Canon’s Digital Photo Professional. To use a RAW file from the burst in Lightroom, you must first extract selected frames using either the camera (see the image above), or with Digital Photo Professional. I very much wish it would just write the individual RAW files to the card when shooting.

Using DPP is also quite convoluted, as the burst stacks appear as regular RAW files, and when you open them, it simply processes the image captured right when you pressed the shutter. To access the other frames, you need to select the file, go to the menu and open “Start RAW Burst Image Tool” and then select frames and extract them. There’s the option to select multiple frames and extract them too, and while you’d think it would export all of those as individual RAW files at that point: Nope. It just creates a different Burst Stack file. The end result can sometimes be worth it, but Canon HAS to make usability improvements here, because the processing aspect here is simply awful.

The second potential drawback of using the RAW Burst mode is that it really is only for capturing that one moment. After shooting, the camera has to flush the entire buffer, save it to card, and then re-fill the buffer on the pre-roll, so there is a delay of a couple of seconds after triggering the RAW burst before you are able to shoot again. So, if you are planning on shooting a burst and then immediately continue shooting, you will be unable to do so. Despite the drawbacks present, it is a nice feature to have in the right circumstances, but I think Canon can improve the implementation, especially with regards to file handling and software.

Leave a Reply